The Social Impact of Food Waste

Exploring the connection between food waste and food insecurity in canada

As we search for ways to improve the relationship that we all share with our planet, we must also take a good hard look at the relationship that we have with our food.

Food waste itself can be a complex issue. Perhaps, next to the looming threat of plastic pollution or the growing shadow of textile waste, our heaps of food waste may sometimes go overlooked or even ignored.

It truly speaks to the complicated and unhealthy nature of our relationship with the modern food system when we recognize that 40% of all the food that we grow and produce here in Canada gets tossed in the trash and yet 4 million people still suffer from food insecurity.

To break it down further, that’s 1 in 8 households in Canada that are food insecure, with the impacts of the pandemic causing further strain on communities while increasing our reliance on more waste-intensive fast food and takeaway options.

Whenever discussing food insecurity, it is important that we also pause to recognize how BIPOC communities continue to be disproportionately impacted, as the inequities of our system so often reveal the connections between social and environmental justice. A recent study by PROOF and FoodShare has shown that Black households are 3.56 times more likely to be food insecure than white households here in Canada.

In some ways, many of us may have lost our ability to truly see the value in our food. There is a certain feeling of helplessness, or even shame, built into our relationship with what we consume, and what we are quick to toss away.

Both in Canada, and likewise on a global scale, we simultaneously identify overproduction and food surpluses in some areas while food shortages occur in others. At the exact same time that so many of our community members face a lack of sustainable access to healthy and nutritious foods, Canadians are also wasting nearly 2.2 million tonnes of edible food each year. In total, this costs us an excess of $17 billion collectively and costs the average Canadian household more than $1100 per year.

It is no surprise that all this wasted food comes with such a high price tag, but it isn’t only a matter of lost funds or profits that we should be concerned with. What is wasted goes far beyond the food product itself and the value of the item on the shelf. When we simply toss our food away, we “are also wasting all the resources, water, energy, land, and labour required to grow, harvest, transport, store, process, and cook our food.”

The Environmental Impacts

Did you know that each year, 56.5 M M tonnes of Co2 equivalent emissions are attributed to food waste here in Canada?

Altogether, food loss and waste (FLW) accounts for nearly 60% of the food industry’s environmental footprint. What’s more is that a good percentage of this waste is considered “avoidable,” meaning that these products make it to the store but are never actually purchased by customers. On the other side of the coin, we have “unavoidable” food waste such as animal bones or other by-products that were always planned or expected to be wasted. This tends to occur when food is broken down, cooked, and processed.

According to research by Second Harvest and Value Chain Management International, 32% (or 11.2 million tonnes) of this lost and wasted food could be rescued to support communities across Canada. They record the overall value of that avoidable waste at $49.46 billion but make a note to acknowledge that the figure doesn’t go so far as to include production costs like water, energy, labour, or disposal fees.

One major concern also comes from the fact that once the food waste finds its final home in the landfill, it breaks down and releases methane gas into the atmosphere which is 25 times as damaging as carbon dioxide.

The research also points out a few other facts related to how we value our environment and the food it produces under our modern food system…

· Apples rot under trees due to labour shortages or low prices making it uneconomical for farmers to harvest

· Surplus milk goes into sewers

· Thousands of acres of produce are plowed under due to cancelled orders

· Fish are caught and then tossed back into the water to die if they don’t match the quota

Just by scratching the surface, we begin to see how the issue of food waste is directly linked to our current systems of economic growth, our approaches to environmental sustainability, and our efforts to foster social equity.

Moving forward, we encourage the shift away from our current “take-make-waste” model towards a circular economy system that prioritizes environmental, social, and economic sustainability. Our team at A Greener Future believes that this must also be supported by a circular food economy embodied by individuals, communities, and organizations alike!

Community Resources

Black Creek Community Farm increases access to healthy food in our community through their programming and food distribution projects.

FoodShare facilitates numerous community-centered food justice programs across Toronto. Through their Good Food Box program, they work side-by-side with organizations across the city to deliver urgently needed fresh food to folks facing heightened food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not Far From The Tree is a fruit-picking and sharing project. NFFTT works to connect generous tree registrants with excess fruit to volunteers in their community who are willing to pick and share it. The bounty from each fruit pick is split 3 ways between the tree registrant, picking volunteers and social service agency partners, including food banks, community kitchens, supportive housing programs, and community health centres.

Second Harvest redistributes nutritious, unsold food from across Canada to charities, non-profits and Indigenous communities in every province and territory. Their free, essential service helps nourish people through school programs, seniors’ centres, shelters, food banks, and regional food hubs

The People’s Pantry Toronto is a completely volunteer-run, grassroots initiative providing home-cooked meals to individuals and families across the GTA who have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

You Should Check Out

Similar Blog Posts

How Food Packaging Waste contributes to plastic pollution

Food packaging accounts for 33% of litter found at A Greener Future’s cleanups

When we hear the term “food waste” we think of, well, food. But, what about the plastic our groceries come so neatly packaged in? Or the plastic straws, cutlery and containers that come with our takeout meals?

In Canada, 3.3 million tonnes of plastic end up in landfills each year, with plastic packaging making up half of that total. The lifespan of plastic packaging is often incredibly short, with most packaging being thrown out in six months or less. Scientists have predicted that if things don’t change, Canada will generate an additional 450,000 tonnes of plastic packaging waste by 2030.

By our most conservative estimations, 33% of the litter we pick up at A Greener Future’s cleanups (excluding cigarette butts) is food packaging. This includes things like water bottles, grocery bags, plastic straws, cutlery and wrappers, but doesn’t include unidentifiable plastic and foam pieces, some of which certainly come from food packaging.

A Greener Future has picked up more than 13,000 straws from the shores of Lake Ontario.

The COVID-19 pandemic is only exacerbating the problem. With new restrictions preventing consumers from bringing reusable cups and containers to restaurants, coupled with frequent lockdowns preventing indoor dining, the use of single-use plastics including takeout containers has grown by 250 to 300 percent since the beginning of the pandemic.

Takeout containers come in many different forms, and some are harder on the environment than others. Two of the most common types, black plastic food trays and polystyrene (foam) containers are both notoriously difficult to recycle.

In an effort to reduce their impact on the environment, some restaurants have shifted to using biodegradable plastic containers - but these alternatives are not as “eco-friendly” as they may sound. Biodegradable plastics require very specific moisture, heat and oxygen conditions to break down properly - conditions that our local composting facilities often cannot provide. These containers also frequently contaminate local recycling streams as they are difficult to distinguish from regular plastics. Because of these failings, biodegradable packaging is sent to landfill despite its deceiving name.

Unfortunately, with more waste comes more litter. Toronto experienced an increase in littering in its parks and beaches during the summer months of the 2020 pandemic as restaurant and bar closures drove people to socialize outside. Unsurprisingly, single-use PPE was found among the litter mid-pandemic, but the City also reported finding coffee cups, napkins and, you guessed it, food containers.

Reasons for optimism:

Plastic pollution is one of the environmental movement’s greatest challenges, but we’re at a pivotal moment in time where policy, business and product innovation are beginning to align with science. We’re now better equipped to take on the plastics crisis than ever before.

Extended Producer Responsibility

In 2020 we saw the Ontario government announce plans to transition its Blue Box recycling program to an Extended Producer Responsibility model. What this means is that producers will take responsibility for recycling the waste they create, taking the burden off local municipalities and taxpayers. It is believed that this new model will encourage innovation in packaging design, to make packaging easier and more efficient to recycle, since the companies creating the packaging will also be responsible for recycling it.

The transfer of responsibility to producers is expected to begin in January 2023, with full producer responsibility taken into effect by the end of 2025.

Canada’s ban on single-use plastics

Another reason for hope is Canada’s proposed ban on single-use plastics, which is part of a larger effort to achieve the government’s goal of achieving zero plastic waste by 2030.

The ban on single-use plastics will focus on six “problem items”, including grocery bags, straws, stir sticks, six-pack rings, and food packaging made from hard-to-recycle plastics.

Though there is still much work to be done, this is certainly a step in the right direction to curb the amount of food packaging ending up in landfills and our environment.

The regulations for this ban are expected to be finalized by the end of 2021.

Innovation in packaging

As unsustainable models of food packaging are phased out, opportunities for innovative sustainable food packaging are endless. Some companies are opting for compostable, or even edible, packaging, while others are making packaging that is easier to recycle. Further innovations have led some to adopt refillable packaging schemes to reduce waste.

A Toronto company called Suppli hopes to make single-use takeout containers a thing of the past by using a circular economy model to take out packaging waste. Suppli has partnered with local restaurants in Toronto to offer reusable takeout containers. Consumers can create an account with Suppli,and then order from a participating restaurant to receive their meal in a reusable container. When finished, containers can be rinsed out and brought to a local drop-off point where they’ll be collected for cleaning and reuse. How cool is that? Now we can support our local restaurants without the waste!

What can you do?

Now that we’ve addressed how the industry is tackling the food packaging problem, let’s talk about what we can do as consumers.

Support your local zero-waste shops & refilleries: we’ve compiled a directory of our go-to spots throughout the Lake Ontario area.

Opt for plastic-free produce when you can: even if you don’t have a specialty zero-waste store in your area, big box grocery stores will have plastic-free options for produce. When possible, purchase plastic-free and bring your own bags to avoid single-use grocery bags at the checkout.

Write or Tweet to your local grocery stores: Tell them that you’d like to see more plastic-free options at their store. Companies will often make changes that will make their customers happy. Even one email can make an impact!

Support your local restaurants & ask them for more sustainable packaging: Now more than ever we need to support our local restaurants. While you’re at it, why not ask them if they’ll consider transitioning to a reusable packaging scheme?

Join us at a litter cleanup: As we mentioned earlier, ~33% of what we find is food packaging. We need help cleaning up our local parks and beaches to protect our water and wildlife. Follow us on Instagram for updates on our litter cleanups.

< back to Food Waste Action Guide

You Should Also Check Out

Similar Blog Posts

What is the environmental impact of food waste?

We're wasting more than "just" food

We all know we shouldn’t waste food. If you’re like me, you probably feel a pang of guilt when you have to throw away food you’ve accidentally let spoil. It’s true that household food waste is a serious issue; with Canadians wasting about 2.2 million tonnes of food at home. We can all do our part to reduce our individual food waste, but this issue far extends to food that gets thrown away at home.

What’s the big deal about food waste anyway? Well, it’s more than just food that gets wasted - it’s also the water, fossil fuels and land used for producing and transporting our food. Our food can travel thousands of miles before reaching our plates after being grown, processed, packaged, shipped, sold and, finally, bought by consumers like you and me.

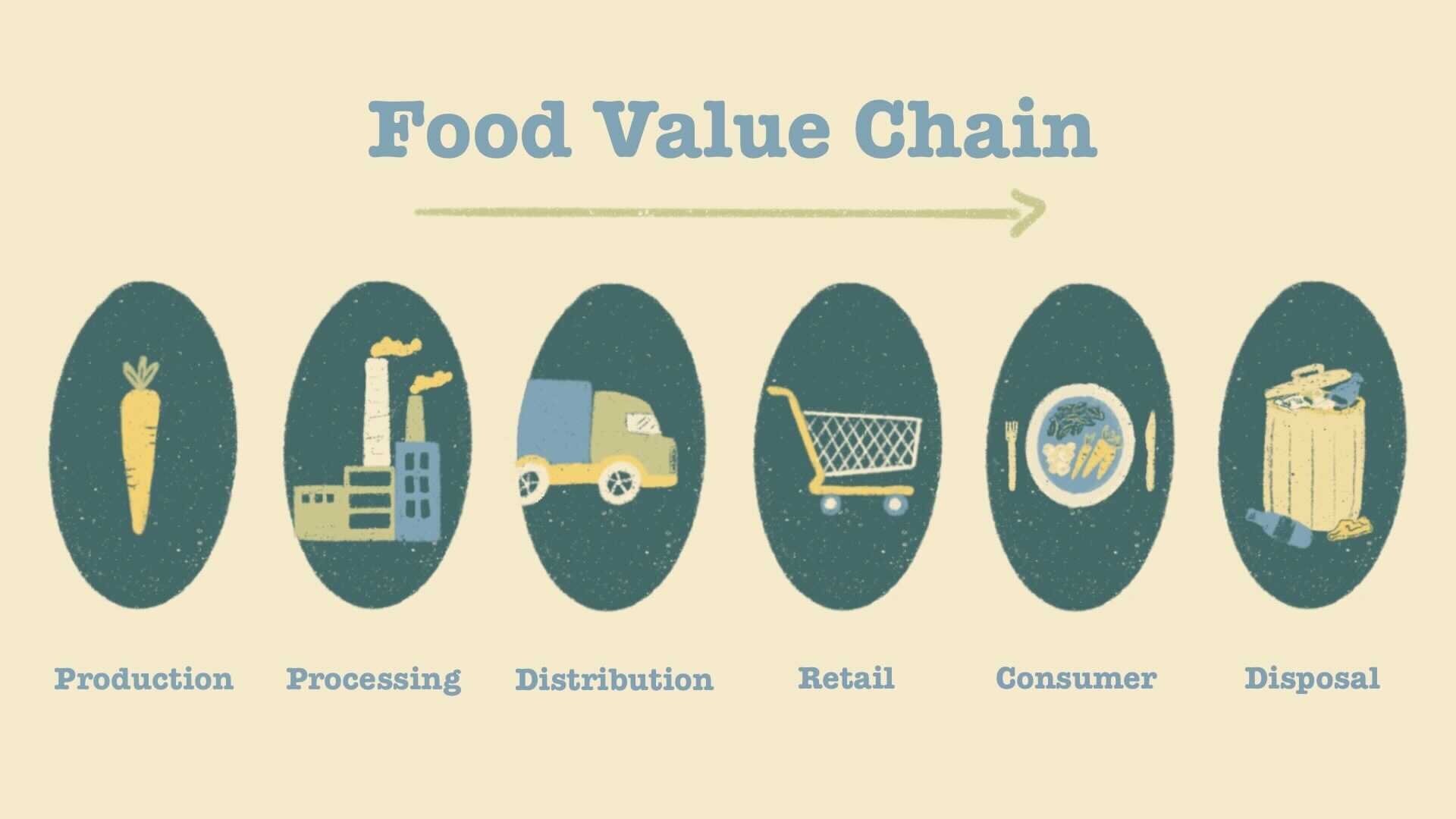

Food waste through the value chain

We’re so accustomed to seeing our food neatly packaged in our local grocery stores that it can be easy to forget about all of the other steps it goes through in the value chain before ever reaching our plates. Growing our food and getting it from “A” to “B” can be resource-intensive.

What’s worse is that some food never makes it to our plate at all. The FAO estimates that 14% of all food produced is lost before it ever reaches the consumer. On top of all of that lost food, we have to acknowledge all of the wasted resources that went into producing it in the first place.

Food Loss vs. Food Waste

Before we delve any deeper into this issue, let’s iron out some of the verbiage we’ll be using. Food loss and food waste are not synonymous.

The term “food loss” is used to describe food that has been lost on the farm it was grown, or throughout the supply chain before it reaches retail markets, like grocery stores. Broadly speaking, food loss occurs when food is spilled or spoiled, or if fruits and vegetables don’t meet the aesthetic standards required to be sold in grocery stores.

On the other hand, “food waste” refers to food that “completes the food supply chain up to a final product, of good quality and fit for consumption, but still doesn't get consumed”. Food waste typically occurs in retail and home settings, where food is discarded for a variety of reasons.

Up to 35 percent of food in high-income economies is thrown out by consumers

Resources

When food is wasted, all of the resources used in the value chain are also wasted.

Water

Because we live on a “blue planet” it’s easy to take our water resources for granted. There are 326 million trillion gallons of water on Earth, but only 1% of all freshwater is accessible for human use, the rest is “locked up” in glaciers and ice caps. We all know that water is a precious resource, but we don’t often think about the corresponding water that is also thrown away by wasting food. Food that is lost or wasted along the value chain accounts for one-quarter of all freshwater consumption worldwide.

Here are some fast facts:

1 hamburger requires 3000 litres of water

1 egg requires 236 litres of water

1 cup of coffee requires 15 litres of water

1 salad requires 95 litres of water

By doing our part to reduce food waste, we can also help to prevent wasted water. Understanding the water footprint of different foods can also help us transition to a more sustainable diet in general. According to the Water Footprint Network, it takes more than 15,000 litres of water to produce one kilogram of beef, but only ~300 litres to produce the same weight in vegetables.

Energy

It has been estimated that if food waste were a country, it would be the third highest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the world, behind the USA and China.

Getting food to our plates requires a lot of energy. Greenhouse gases are produced at every stage of the food value chain. Starting at a farm, greenhouse gasses are emitted from machinery, fertilizers, manure, and even cows themselves!

Energy is then needed to process raw materials into final food products. Next comes the emissions from transporting food products across domestic and international borders. Finally, the food reaches grocery stores and markets, where energy is used for refrigeration and other retail processes.

Across all value chain levels, food waste in Canada produces a whopping 56.5 million metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions every year.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t stop there. If food is wasted and ends up in landfills, it will release methane into the atmosphere as it breaks down. Methane is a greenhouse gas with 25 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide. In Canada, 20% of our national methane emissions come from landfills.

Many cities in Ontario are fortunate to have access to municipal composting facilities, which, if used properly can reduce the amount of food waste in landfills, thereby reducing methane emissions. However, despite having more than 90 municipal green bin programs in Ontario, over 60% of Ontario’s food waste is still being sent to landfills.

According to research by Project Drawdown, if composting levels increased worldwide, we could reduce methane emissions from landfills by 2.1 billion tonnes by 2050.

Land use

Using industrialized agriculture to try to feed the world’s more than 7.6 billion people requires land and lots of it. More than half of the world’s habitable land (free from ice or deserts) is used for agriculture. Creating agricultural land often requires deforestation or burning, which destroys biodiversity and releases greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere.

Some foods require more land use than others. Lamb and beef require the most land per kilogram of meat, whereas many fruits, vegetables and plant-based proteins require far less.

According to the FAO, 1.4 billion hectares of land are used to produce food that will later be wasted. Beyond this, we must also remember the processes that went into cultivating that land for agricultural use, which are also wasted if the food is not consumed.

What can we do?

When faced with a challenge as big as food waste, it can be easy to feel overwhelmed. It’s clear that the food industry has some work to do to combat food loss and waste, but there are also simple actions that we, as individuals, can take to do our part.

Here are some quick tips:

Understand your diet’s carbon footprint - Quiz: How Much Does Your Diet Contribute to Climate Change?

Eat local - purchase food grown close to home where possible

Compost using municipal facilities or backyard composting

Check out Love Food Hate Waste Canada for ideas on how to prevent food waste at home

Buy “ugly” or imperfect produce - our friends at Bruized upcycle imperfect foods into healthy eats

By understanding how our food reaches our plates, and all of the resources that go into producing it, we can make informed choices to avoid wasting it.

Fundraising Coordinator, A Greener Future